Queer: We’re off the edge of the map - here be dragons - J.C. Rycroft

26 Jun 2023Writing character is a strange blend of authorial intentionality and fictional wilfulness.

Sometimes the author can direct the character, write them their grievous backstory wound and illustrate their defining false belief that leads them astray. Make them say the most entertaining things. Tweak an expression here to give away an emotion. A marionette in an author’s hands.

And other times, the character tells the author in no uncertain terms who they are, even if it makes an author’s life tough.

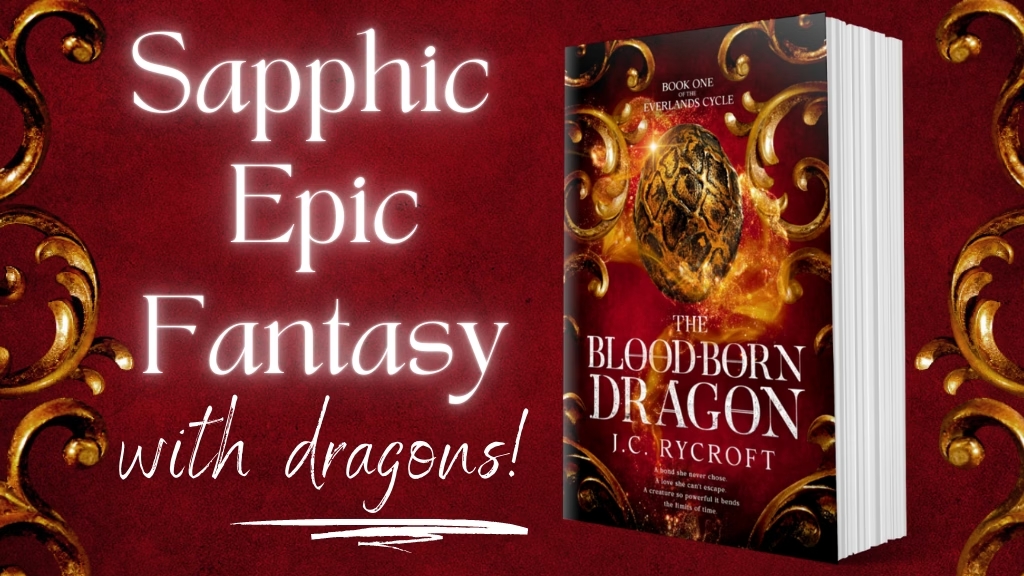

And so it is with Des, the main character of The Blood-Born Dragon, my new sapphic fantasy novel.

She’s a smart cookie, our Des – a sellsword who accidentally hatches a dragon. My dev editor commiserated with me about writing smart characters, because it generally means that the author needs to exercise all their brain cells to keep them readable and believable. But beyond that, she’s determinedly queer, though she doesn’t describe herself that way. Indeed, part of the point for Des is that she doesn’t feel like she has some fundamental centre that defines her. She has a history as a player – an actor in the world she inhabits – and so is incredibly adaptable. She’s had to be.

And it means that when she talks about her sexuality, she’s not naming some internal truth, and hoping for recognition. Granted she doesn’t talk a lot about her sexuality, given she’s pursued by entire armies for most of the book (which should not be taken as code for zero spice!). Des just finds that she’s attracted to some and not others, but that this follows no real predictable lines, particularly not based on gender. She’s unrelentingly drawn to Liv, agonisingly difficult as that relationship is, and to graceful Joseph. But even though it might have made her life a tonne easier, she’s not attracted to Petrus, although she can appreciate how handsome he is and even though he’d have married her if she’d crooked her little finger. But those seeking a naming of identity from her – or from Liv, her enemies-to-lovers, second-chances love interest - are likely to be disappointed.

By some standards, Des and Liv’s failures to name their own identity on-page suggests they might be ashamed of their own desires. I’m not so sure.

I spent many years studying queer theory (alongside a bundle of philosophy and cultural theory which is both a boon and a barrier for writing fantasy!). I was inspired by some of the work in the history of sexuality, which observes that historically, desires were much less imagined to be pinned to and defined by some consistent, ahistorical inner core – a thing we might call sexuality, as we might understand it today.

Rather, desires happened, and some were acted on, but they weren’t really thought to be defining of who someone was. They were often thought of as fleeting, passing even – and as quite separate from official attempts to control and pin down sexual behaviour into heteronormativity through marriage. And so, Des’s refusal to name her sexuality might be understood as entirely correct for a fantastical but definitely historical setting.

Names for sexualities can be vital: it helps us share with others the difference of our sexuality, and have them recognise it. But even our most generous names for identity have historically wound up delimiting how desire, love, and the draw between people, can be understood, described, and experienced. Which is part of how what was once ‘gay and lesbian’ became the more capacious QuILTBAG, as we’ve all come to appreciate more about the dimensions of love and attraction.

No matter how capacious our labels, though, there’s always something of the unspoken and the unsaid - even the unspeakable - in how we live out our desires. Sometimes this might be most easily graspable the changeability in a characteristic that might otherwise have been understood to be defining of an entire life, from birth to death. As someone whose desires have shifted and morphed over time, I feel this one particularly.

Sometimes it’s the complex interplay of the desire for others and the desire to be something for others. Sometimes it’s the complicated attraction to someone who repeatedly hurts us and we know is not good for us (hi, Liv!). Sometimes it’s the stitching together of desire and attraction against what the acceptable list of desired objects might be – to an act, a body part, to power.

In many ways, I feel like the fuzzy definition of ‘queer’ – the Q that often gets left behind on the LGBT acronym - is an attempt to point to and make space for these complicated, unclear, uncertain, and unpredictable manifestations of desire, and love, attraction and even gender and identity itself.

Every now and then, a commentator will make some grand claim about how characters in a book must self-identify as particular identities on-page in order for a book to ‘count’ as LGBT or queer. Or that an author must self-identify publicly. It seems to me that this issue echoes the demands of coming out – the requirement to make our desires, our loves, our attractions, transparent and recognisable to others. But for many of us real life people, this is no easy feat, and a never completed task.

So as complex as it has made situating my book baby in the bookish world, it feels important to have some elements of this fuzziness reflected on the page as well.

But it hasn’t always made it easy to pitch my book, whether to retailers or audiences!

I love that the terms ‘sapphic’ and ‘achillean’ have arisen in book circles to help name not just characters, or identities, but desires and dynamics between characters. Des and Liv’s relationship is definitively sapphic – they’re both women, even if they have quite different, if both resistant, relationships to the concept of womanhood that exists in Rescalin. And even if Squid, Des’s bonded dragon, describes their relationship as ‘love-and-hate,’ the slow burn and occasional (at least in Book 1) spice is definitely present. So that one has felt safe.

But if it’s proven difficult to find recognised terms to name Des’s identity, it’s made it complex to work out how to categorise the book itself by extension. I sat in front of my computer many times trying to select categories on retailers to help visibility. I’ve considered classing the book as ‘bisexual,’ but in this book at least, there’s barely a mention of Des’s desires for men, let alone that for her, gender isn’t really the point. (There is one little mention of a ‘graceful Joseph,’ a shout-out for my multi-gender-attracted compatriots out there!). But given the focus is on Des and Liv, rather than an array of partners, that didn’t seem adequate. I wound up putting The Blood-Born Dragon into ‘lesbian’ fiction, although neither Des or Liv are lesbians…

But for me, this is one of the most exciting elements of the decade or so of self-published fiction we’ve seen – we’re seeing a multitude of desires, loves, partnerings, attractions, sexytiems, and so on, all on the page. Without the limitations of a trad publisher sitting behind the text and the risk to their business of being criticised for reflecting, well, queerness in all its glory, indie authors are offering up a thousand different ways to understand, well, the queerness of desire.

That they’re still all forced to wedge themselves into categories that can barely hold them is probably half the point, really: queer desire will always explode out of whatever seeks to contain it.

And for Des, that explosion of queer desire on the page may be inconvenient and unhelpful, given she’s put a mountain of work into getting over Liv…. But it’s no more able to be denied for all of that. And that’s our Des: testifying queer to the very end.

The Blood-Born Dragon was released on the 30th April 2023 and is now in KU, ebook on Amazon, and paperback everywhere I can manage. A prequel novella, A Hired Blade, is also available: free on signup to my mailing list, or on all good retailers.

About the author

I’ve written stories for most of my life.

Ever since I was a child, I’ve been entranced by stories and storytelling. I am vastly entertained by the unchosen heroes who can’t quite believe it, by encounters that are funny by accident, by desire that pokes its head where it’s not quite wanted (why hello queerness fancy meeting you here… again!), by fury that fills the soul and cannot be tamed. I love some meat on the bones of a story, but I want a rollicking good read. So that’s what I write.

I’ve always loved, too, imagining other places, other ways of being, other ways the world could be built, other ways of thinking of the time, and other ways that people deemed others might relate. So it’s no surprise I’m drawn to fantasy and sci-fi as a genre. Imagining elsewhere and who might live there are some of my favourite things to do.

My PhD trained me as a cultural theorist, which means I have some pretty complex tools for understanding the world within reach. But it also means that I know that the ways that we talk about things – from our relationships, to the natural world, to political structures – make some things imaginable, realistic, realisable, normal, and real. And other unimaginable, unrealistic, impossible, weird-as-fuck dreams. We talk about ‘world-building’ in fiction all the time – but I think all of the fantastical worlds we read and write shape our own as well.

So if this sounds like a ride you’d like to join me on, stick around. The best way to stay in contact right now is via my mailing list or on Facebook. But I’d also love to hear from you directly, so please don’t be shy.

I live, love, play and write on Wadawurrung land. I pay my respects to elders past and present, and acknowledge the ongoing horror of colonization. Sovereignty over this land was never ceded. It always was, and always will be, Aboriginal land.