Reflections on Queerness in SFFH and The Wings of Ashtaroth

15 Jun 2023Artists in a Dangerous Time

When I worked as a manager at a hobby store shilling comics, boardgames, action figures, and the rest; the owner once gestured to the store and its varied offerings and said to me that what we really sold were dreams. There was no prescription placed on what the dreams were of, precisely, for that is always unique to the dreamer, but the fact that the very invocation of dream stuff seemed to change the air and transform the space of the store into a place that meant something deeper, speaks, I think to the value of stories queer and otherwise.

As a trans artist, it’s a strange feeling to address the question of what’s queer about my writing. Surely, I want to say, anything I create will have an innate and ineffable queerness to it—a feeling or an atmosphere or a perspective that seeps into and through my words like salt inside seawater. But as a reader as well as a writer, I find it’s not so simple as being able to tell in some concrete way, whether the mind on the other side of the page is writing with a queer eye or not. It would be more than a little alarming (not to mention constraining) if we could determine such things. As a trans person alive and online as of writing this, it calls to mind current attacks on trans people—particularly trans women—and McCarthyist attempts on the part of Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFS) to investigate the genitalia of strangers.

The same pernicious and prurient desire that brims at the edges of TERF-fueled accusations of transness seems to undergird conversations about queerness and the ownership of identity—an internet ever in search of the gotcha moment when a given marginalized creative makes a mistake or reveals themselves as “less than” and therefore a fraud in some way. One needs only scrape the surface of Twitter discourse, for example, to find instances of bisexuals and asexuals being accused of not being genuinely queer, or of cases like Isabel Fall’s in which a queer artist’s self-expression is dismissed and denigrated as harmful to the rest of the community. The tightrope of identity has always been a thin one, and rarely is there a safety net to catch us.

What I mean here is not that queer writers don’t offer new and challenging perspectives, but that there’s a tendency to collapse and flatten queerness—a desire to measure and circumscribe and define it—that seems contrary to its very nature. As a commodified identity, queerness becomes susceptible to a sense of ownership, of possession. But if my words contain traces of whatever uniqueness my queer identity imparts to me, these traces are of a kind particular to my singular perspective and not unilaterally shared across the spectrum of artists and individuals with whom I share that identity. This does not mean they won’t have a resonance for other queer people, nor that we can’t talk about shared experience, but that to limit queer artistry to a set of prescribed rules, understandings, and symbolisms is to miss much of what is valuable about both the mutability of queer identity the power of art. For some, to admit that queerness might look different across the aisle is to admit that one’s possession of queerness is fragile and transitory. Unable to clasp our identities close to our chests, we are set adrift without the political surety that we are, above everything, Queer, and through the loss of that capital-Q Queerness, neither representative of the whole, nor part of a community that can be defended from hostility.

And yet, as queer people and artists, our bodies as well as our words are always already both essentialized and political. We are read politically. We are interpreted politically. Our work and our creative output is measured against whatever the current yardstick is to determine queer authenticity. And when we are seen to fail, or a character or real person falls short of that yardstick, it is considered a failure for the entire community. It is in this way that queer works of fiction and the characters contained within that fiction, are pressured to uphold an impossible perfection whose exact nature is never static. Queer characters must always be and do good (however “good” is defined). Queer characters must always challenge or educate.

Conversations abound about what we should or shouldn’t be writing. Speculative fiction that depicts “queernorm” universes in which bigotry against queer people is absent are lambasted as “safe,” as pandering, or as childish attempts on the part of authors and readers to bury their heads in the sand. Fiction that engages with the sometimes horrifying reality of queer people’s lived experiences is silenced by accusations of trauma mining or of being harmful to a vaguely defined public.

I am conscientious, also, of the fact that any work that includes queer or other marginalized characters, may be dismissed as “political” in some essential meaning of the term that is for some reason never applied to non-marginalized works and characters in the same way. Rarely, if ever, is an author interrogated for including a straight character on the basis of “politics,” yet the art of marginalized creators is often dismissed for exactly this reason. How many of us have read, received, or even written a review that included some variation on the phrase, “this was a little too political for me,” or “the politics took me out of it.” What, we might ask, was too political about the work in question? If the answer is simply the inclusion of characters who look, sound, or feel differently than us, perhaps we might be urged to reassess what, to us, makes one body political and another not? Why is my existence political, but yours is not?

Politics is a verb that acts upon and adheres to bodies; it is not something that resides within them. And yet by our very existence as people informed by culture, by family, and by our experiences, we are each of us made political, just as the choices we make in terms of our creations are read politically.

There is no one queer style or one queer voice, or even one set of queer expectations when it comes to art, and this is in part because there is no universal politics of queerness. All the same, even as I write these words and assert that there is no univocal queer voice that can be sensed, inexplicably, from beyond the page, there remains a power in listening to others with whom I feel on some level a sense of shared struggle or memory or resonance. If there can be, to reference medievalist Carolyn Dinshaw, a queer touch across time, is it also not possible for there to be a queer touch across the page? A kind of queer harmonics. Perhaps our voices don’t so much align in undifferentiation, so much as hum, for however a brief an instant, in synchronicity.

It occurs to me that whether a queer person is drawn to stories that whisk them away on a cloud of fancy, or those that probe the so-often painful edges of what it means to be queer and human, most of us are on some level in search of something like at-homeness. The precise definition of what being at home means, of course, will shift: is it a cozy feeling of belonging that we feel was denied us, or which reminds us of the potential for queer flourishing? Perhaps we even experienced a cozy at-homeness during childhood and feel compelled to share that wonder with others. Or is it an acknowledgment of what we feel to be the inherent weirdness of queer existence (the unheimlich—Freud’s unhomely/uncanny—made its opposite by a group of people whose existence is perennially uncertain and liminal)? For me, reading and watching horror is a kind of comfortingly disturbing experience. The connective tissue that binds us to stories is deeply personal: a returning-to, building-up, and even rending-apart of the experiential fabric that makes us and the societies we live in. To view any one piece of fiction as capable, therefore, of representing each and every varied experience is to misunderstand our relationship(s) to art, but also to undervalue difference itself.

Magic comes in when we do recognize commonalities across the page, but it also emerges through engagement with a difference by building empathy. Differences of approach, of view, of voice, and of experience can challenge those reading a written work of fiction to self-reflect and deepen critical thinking. It can also be jarring, revolting, saddening, and rage-inducing. Neither of these things precludes the other, nor do they preclude enjoyment.

My own stories are dreams of a kind—my dreams, certainly, and my nightmares as well—but for a time, at least, through reading, they also become yours. The hum synchronizes before dispersing, and pieces of ourselves remain to drift inside the other: a queer touch across the page. An uncanny voice in the darkness describing the outlines of a home.

My Queer Context

The initial plot fragments of The Wings of Ashtaroth came to be when I was in junior high when I was around fourteen years old. I held off writing the book for a long time because I knew it would be complicated and I didn’t want it to be my first finished novel.

Spoiler: it was my first finished novel (though I didn’t write it until I was in my mid-late twenties. I’m in my late thirties now).

As a teenager growing up in the late 90s and early 2000s, I really didn’t have access to the same resources that people do currently. We didn’t have internet at home till I was in university, and so if I wanted to learn anything about what it meant to be queer (and particularly trans), that meant looking up whatever I could in our school library/computer lab. By high school, I had a bit of an edgy chip on my shoulder and didn’t give two shits what people saw me looking up (and besides which, there was a girl who often sat beside me and spent her lunches exchanging e-mails in a pornographic roleplay).

I only learned from friends that others in our school were afraid of me. This, to me, both was and wasn’t surprising.

I wasn’t surprised because in junior high I’d very much cultivated a reputation as a weirdo (not a mean or creepy weirdo, but I was aware that any degree of eccentricity put people off). I did things like wear empty potato chip bags as hats and patrol the school with my fellow oddballs (most of whom later turned out to be queer) as the self-proclaimed kings and queens of the school. We had a whole classroom that at lunchtime became our domain and we had an entire set of rules of conduct both spoken and unspoken, such as that we would only exit through a window, never the door. When popular girls would inch into our radius out of curiosity, their boyfriends would express a vague worry that some of our strangeness would rub off on them, but no one bothered us. For reasons that I still don’t understand, our very patient gym teacher would let my friend and I sit out of any sport we didn’t like (which was all of them except badminton), and instead we spent gym class sitting on the stage and making up ridiculous songs. People (including the school staff) let us be. It was honestly the best school I ever attended, and I’m still enormously grateful for the teachers and administration. Our queer camp theatricality was cherished rather than reprimanded, and I suspect that much of that was because the school understood what we were even if we did not.

At high school I was surprised that people were afraid because I had very much retreated into myself, returning to something more like the shy and sullen person I’d been in elementary school (thanks puberty!). We didn’t patrol the school and I didn’t wear any chip bag hats. At most, our nascent queer friends' group hung out under the stairs trading food. What scared people, it turned out (apart from my reputation for general strangeness, and the fact that people thought I was a Satanist because I once drew an ankh on a chalkboard), was that someone had seen me visiting a website about being trans. Also suspect was that in one biology class, I’d raised my hand and asked during the teacher’s lecture on “the two sexes,” if we were going to cover people that didn’t fall into either category (the answer to which was a shocked expression followed by no). After this, it was not-so-subtly suggested by my then-boyfriend that I might try to be a little more normal, a little more like a girl. The spectre of transness (though I’m sure my fellow students wouldn’t have used that terminology at the time) was enough to cause at least a minor panic—a reverberation that I myself was perhaps naively unaware of till it was pointed out. It just seemed incredibly silly that anyone should care about these things, and anyway, it was my business and not theirs.

I bring all this up for what I think is an important context that a younger generation of queer people (particular trans people), aren’t aware of. It wasn’t just that I lacked the resources and therefore vocabulary to describe who I was, but that the people in my immediate environment also lacked any level of understanding. At a certain point, I started asking my closest friends to use he/him pronouns (I’d already been “Steve” for years) but was met with a variety of negative and paternalistic responses. I don’t blame those friends for their reactions—how can you understand the nuances of someone else’s identity when they themselves don’t even have the appropriate vocabulary to explain it to you? I remember that in desperation I lied to my best friend that I was intersex because I thought that would make her more likely to take me seriously when I said I was a man. It really wasn’t until university, where there was a dedicated centre for queer people of all stripes, that I learned more about myself and about queer identities and history. Suddenly I had a way to express who I was (though I chafed at rigid categorization and still do), and that new vocabulary provided a means to articulate to straight people who I was.

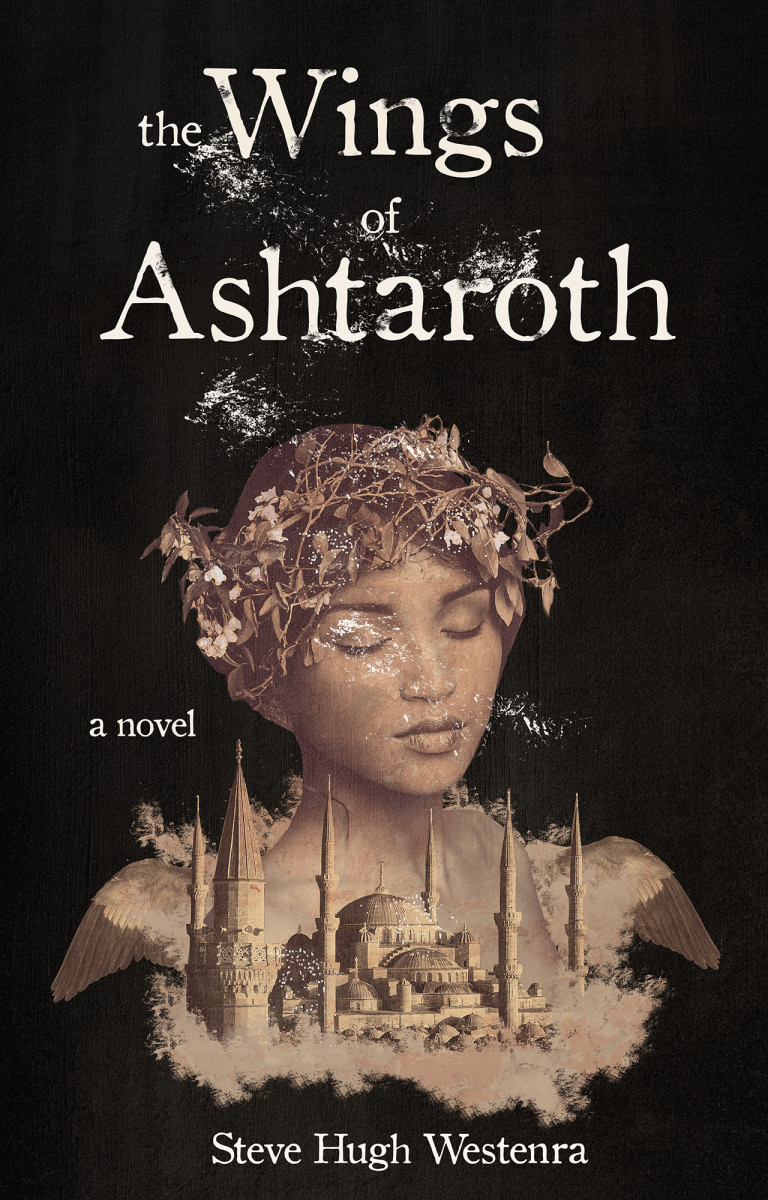

The Wings of Ashtaroth

I think because of my background and the limitations of the information I had access to during my youth, as a writer I’m very much drawn to creating stories in which the lines delineating identity are at best translucent. Most of the characters in my stories wrestle to some degree with where they sit in the world and with who they are. There’s an inbetweeness—a liminality—to who and where my characters find themselves. This is not simply true in terms of queerness, but also nationality, ethnicity, and gender. In Ashtaroth, which takes as its setting a secondary world based partly on the ancient Mediterranean (particularly ancient Carthage and Rome), most of the modern identities and terms we use to describe queerness are complete unthoughts. This is not the same, of course, as saying that queer people as they would be recognized now don’t exist in the world, but that the vocabulary is different and often non-existent. You won’t, for example, find characters identifying as proud asexuals, pansexuals, or lesbians. You will find characters who experience sex-aversion, who are attracted to people across the gender and sex spectrums, and who are women-loving women.

These feelings and experiences have existed across human history, regardless of whether there were terms to describe those feelings and experiences. To pretend otherwise is, to some degree, to enshrine the present as the arbiter of what human beings are and can be. I’ve stated this elsewhere, but it bears repeating that history is not a linear, progressive phenomenon that neutrally plods on toward an idealized terminus. At various moments in time and across the world, people who would now be understood as queer have experienced greater degrees of freedom and acceptance than they do now in the West. At other times, homosexual sex acts have been seen as a natural facet of human existence, while elsewhen and elsewhere being demonized or rendered illegal.

What appealed to me about crafting a world in which something we might today call “queer rights,” is uneven, is that it destabilizes our progressivist understanding of history. Doing this, one hopes at least, prompts us to revaluate the ways in which we’re primed to accept new or modern things as universal goods, while rejecting the past and its people as somehow valueless, or as assumed straight until proven queer. It also allows me to comment on the struggles queer people both have faced, and continue to face.

The thing we call tradition (or history) is so often the battleground upon which contemporary legitimacy is waged. To possess history, to be able to gesture toward tradition, is to be able to argue for what should be done or believed both now and in the future. The argument that queer people are an entirely a modern phenomenon can be mobilized as a tool for dismissal of those same people and their needs. Similarly, the insistence that queer identities have always been oppressed or that they’ve always been described identically to today reinforces that there is a right and wrong way to behave as a queer individual, and that our identities are only ever able to be understood from a perspective of suffering. For me, it was important to explore the ways in which differing levels of cultural acceptance might impact individuals as well as inform (and be informed by) economics, politics, and religion. For example, in the city of Qemassen (the primary location in Ashtaroth), the existence of trans women is accepted, and yet it is severely constrained for economic reasons. Trans women are understood to exist, and are believed when they identify themselves, yet depending on their family, might be pressured back into the closet if their female gender would get in the way of inheritance. Trans women are also victims of many of the misogynistic attitudes that inform the treatment of cis women in the novel. Trans men, by comparison, do also exist, but since their identification as male would be viewed suspiciously as a way for those assigned female at birth to disinherit cis males, it isn’t accepted institutionally. Having made these worldbuilding choices, I was interested in both the limitations and opportunities afforded my trans characters—how would they navigate these realities and how would their own ideas of selfhood and gender be impacted as a consequence of societal norms?

I drew, also, on my own experiences of transness to inform the characters’ perspectives. There’s one moment, for example, when a closeted trans woman reflects on her adolescence and confides in someone that she’s secretly a girl but that for economic reasons she can’t be a girl. This was a variation of a childhood experience of my own. At around seven or eight, I told a local boy that I was a boy too, but that I secretly had to pretend to be a girl (I honestly can’t remember what reason I gave for this, but whatever it was, the boy believed me). It’s one of my earliest memories of expressing anything like transness, and I think the reason it’s stuck with me is a combination of having felt slightly criminal and illicit at the time, while feeling now that it so wonderfully illustrates who open-minded children can be. To further illustrate, perhaps, how nurture can impact the development of bigotry, that same boy would become one of the teenagers who urged his girlfriend not to hang out with our small group of weirdos in junior high.

One of the characters in the novel whose gender I consider the most fraught is my primary POV character, Ashtaroth. This is probably not very obvious to most readers, since nowhere in the book does he overtly identify as anything other than cis male. When I initially wrote the book (about ten years ago), I certainly saw him as a cis man, but when I revisited and edited it prior to serializing it online, I interpreted the character’s gender as more nebulous—something more akin to a contemporary nonbinary or queer person. Since posting the story in serial format online I’ve reflected a lot on this aspect of Ashtaroth’s characterization. This is in part due to some very thoughtful comments by a trans woman who was reading on Ao3. For her, she very much read the character as a trans woman who hadn’t yet come to terms with her female gender identity. This caused me to reassess whether that might be true of the character, but I think there are more layers there that I’m still unpacking. One of the reader’s comments was that she appreciated how I’d written the character, but that Ashtaroth’s effeminate appearance (which he’s self-conscious about throughout the novel) plays into the privileging of trans women who pass as cisgender. This very astute observation caused me to reflect on why, as a trans man, I’d written the character that way, since it had always been part of the novel, even when I’d been a young teenager. What I realized was that I’d written a lot of my anxieties about trans maleness into Ashtaroth. In a way, he was a validation of my own feelings and my own masculinity. Here was a character who no one argued wasn’t a man, and yet was considered feminine, soft, and weak. He wrestled with the same insecurities that I had, without having to feel the burden that had characterized my own adolescent struggles with gender and dysphoria. Although part of me wanted to validate my reader’s interpretation more concretely by having Ashtaroth identify as female in the sequel, I’m still more partial to something less defined, since it captures that inbetweeness I’m so attached to, while retaining both possible readings. Part of me still wants to represent the character in the way that was so subconsciously important to young, troubled me.

Ashtaroth, I think, also differs in a lot of ways from much of the queer speculative fiction that has been released by mainstream traditional presses (and in saying that I absolutely do not mean to denigrate those works or comment on their quality and importance). But there is a tendency (partly, I think, fueled by fear as well as a genuine desire on the part of editors to do better by queer people) to privilege a quite pristine vision of queer lives. There’s a sense that queer characters ought never to do wrong, ought to perfectly embody a particular politics, ought to come into their queerness early and to know it immediately. Queer (and other marginalized) characters must display a popular concept of agency that mimics trends in the depiction of badass girlboss women. There’s a place and an audience for these kinds of works, many of which I myself have enjoyed, but I will warn you that you won’t find these themes or motifs in my work. Queer characters do ugly things in Ashtaroth. They also frequently have ugly things done to them, fail at their goals, and find themselves trapped in systems in which their agency is severely curtailed or circumscribed. There’s also a lot of subtle queerness, with many characters not quite understanding their attraction or their feelings about gender. Some characters who have same-sex relationships later in the series are almost stereotypically straight in Book One. Many, many times, they make choices that I (and much of the audience) would find abhorrent. The depiction of these choices is not intended as an endorsement of them, nor is it meant to suggest that queer people only do bad things, or that we are cruel or contemptuous, or prone to failure. Rather, it was important to me that I approach my queer characters the way I would approach my straight ones, depicting the variety of people who exist within the world while being attentive to the ways in which our particular circumstances can cause us to do truly vile or upsetting things.

Everyone has a very personal and specific idea of what they want from queer fiction. For myself, I’ve approached queerness in a variety of ways in different writing projects—putting it front and centre in my queer camp horror comedy, while depicting what I call an “incidental queerness” in both Ashtaroth and my lesbian Viking novel. What I believe rings true across the board is that no matter the book or short story, each of my works is just as queer as any other because I, a queer person, wrote them. What this means is not that every queer book will be the same, or that it will appeal to every queer reader, but that if there is such a thing as a queer touch across the page, and that if the way I’ve tried to describe my understanding of queerness appeals to you, you might just find that as you read my work, for a moment at least, we’ll reverberate together in synchronicity.

About the author

Steve is a trans author of fantasy, science fiction, and horror (basically, if it’s weird he writes it).

He grew up on the eldritch shores of Newfoundland, Canada, and currently lives and works in (the slightly less eldritch) Montreal. He holds advanced degrees in Russian Literature, Medieval Studies, and Religious Studies. His current academic work focuses on marginalized reclamations of monstrous figures. He teaches the History of Satan and Religion and its Monsters.

In 2018, Steve’s lesbian Viking novel, Ash, Oak, and Thorn, was selected for the Pitch Wars mentoring program and agent showcase. During Pitch Wars, Steve was lucky to receive mentorship from fellow queer author, K. A. Doore.

His queer horror comedy, The Erstwhile Tyler Kyle, was mentored by Mary Ann Marlowe in the inugural #Queerfest class.

He is a SPFBO9 entrant.

Steve is passionate about queer representation, Late Antiquity, and spiders.