Write what you know - Cat Rector

1 Oct 2024Write what you know. It’s a common phrase in writers' circles and has changed in meaning and depth as our conversations around what it means to be a writer have evolved. It means different things to different people, and a few years ago I started asking myself what writing what I knew would look like.

What I knew was this:

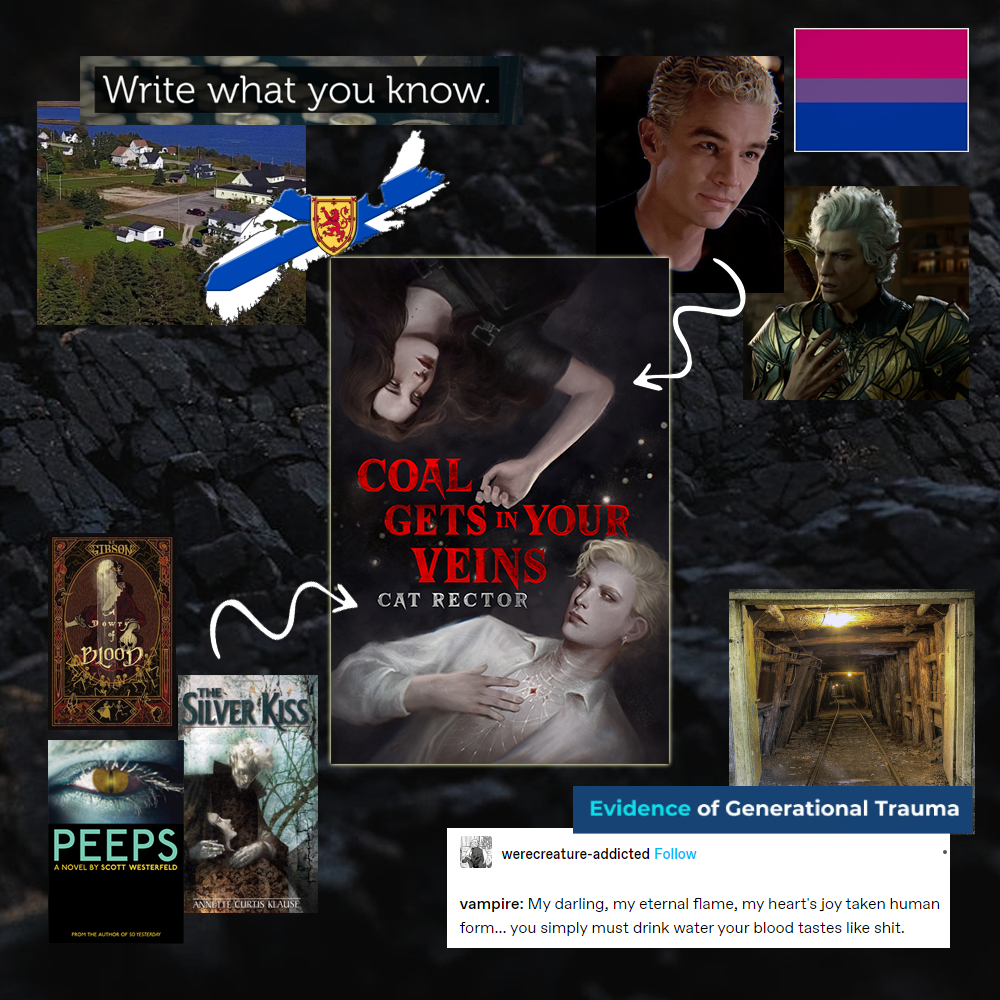

x I had grown up in an isolated and impoverished ex-coal mining village of a few hundred people

x Until I went away to college, I had lived in a ramshakle house that dropped drywall dust into my bed when it stormed

x Our water came from a well, and we lived on top of a coal seam, so what came out of the tap was tinged black and undrinkable

x The people around me were full of compassion for each other, especially when times were tough

x For every good deed done in the name of community, I knew of someone suffering at the hands of someone who loved them, and it was normal

x As much as I had adored the place I grew up, I also wished in my young teen heart that some dashing vampire would find me as I walked home in the night and steal me away from every problem I had

So what does that look like when it’s ground down and shaped into a book?

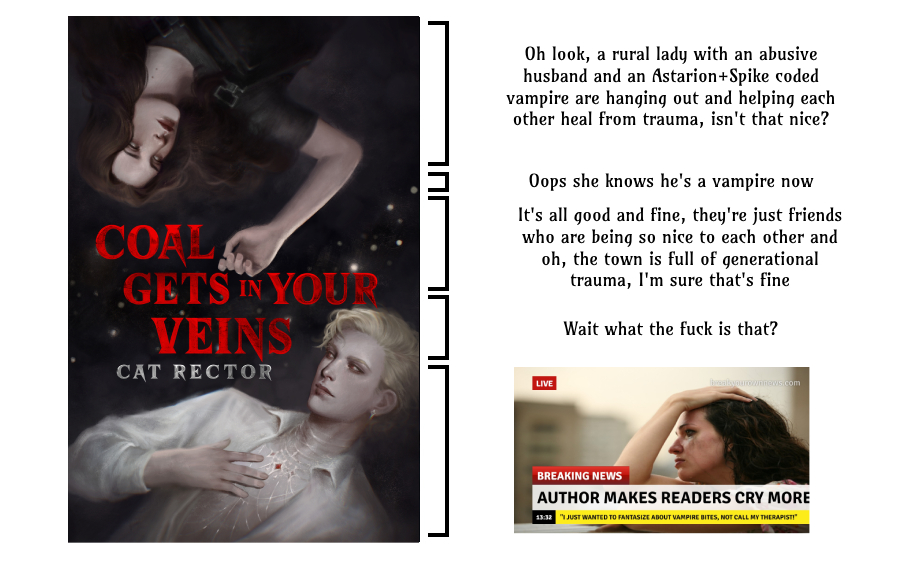

It took several years to find out. Coal Gets In Your Veins is a book about a middle-aged woman trapped in a life she never wanted alongside a man who thought her worthless, and a decades-old queer vampire who had lost everyone who loved him. And of course, the town of Penny Harbour itself, full of pain and hope and coal dust.

The idea didn’t start as something as tidy as that, however. It started as a concept that brought me to two avenues of research: generational trauma and the local coal mining industry. The more I dug, the more this my own history made sense.

Generational trauma isn’t a common phrase. Essentially, it’s the concept that pain inflicted on someone can be passed down the family tree through words and actions, generation to generation. Grandpa went to war, and came home to hurt Dad, who treated Son just the same way. It became Son’s unfair burden to keep from passing his family pain to someone else. We know that pain passed from one body to the next creates emotional and physical scars, and often contributes to mental and physical health issues. (This is a deep oversimplification, and I encourage you to seek out more information later.)

With that in mind, imagine for a moment that you’re walking into a dark, cavernous coal mine. The open maw in the ground slopes down into the earth. You walk and walk. You’ve been walking for twenty minutes into the earth and it’s impossible to know how deep you are. How much rock is above you. You have an oil lamp in your hand, and if you snuff it out, the black will be so all-encompassing that you won’t understand which direction leads back to the surface. You reach the work site. There are people down there with you. Men and boys, covered head to toe in black coal dust, their white eyes sticking out among the dirt. Someone sits to eat his lunch from a lunchbox, his fingers still filthy. Everyone looks worried. Yesterday, a mine in a nearby town caved in. But this is your job. There are no other jobs. You have to be in the mines. You try not to think about it. Try not to imagine if you’ll manage to escape when this mine collapses or explodes or catches fire. Try not to imagine the earth coming down or being trapped for days or the buildup of poison gas. Try not to imagine what your family will do when someday you just don’t come home.

This was the life for the vast majority of men and boys who lived in company towns created specifically for coal mining. A daily series of horror and stress. Many people died from injury or from diseases that are directly linked to coal mining, like black lung. These days, we also understand that stress builds in the body and causes ailments. It’s hard to imagine the kinds of stress that would live under the skin of the man in the mines or the wife who waits to see what will happen today and tomorrow and every day after.

And that pain gets passed to the children, and their children, one day at a time.

Coal Gets In Your Veins takes place in three points of view: Laurel, a middle-aged woman who is finally getting fed up with her emotionally abusive husband. Spencer, a vampire who has isolated himself and is grieving the loss of his loved ones. And Penny Harbour, the (mostly) fictional village whose residents’ blood tastes bad.

The PoV of Penny Harbour is a key piece of exploring the way a place lives and breathes on its own. Each chapter has a different resident of the village, living a day in their own lives. A tiny, bite-sized story that happens outside of Laurel and Spencer’s view but which impacts the story all the same. Each piece has an aspect of truth in it, inspired by something that happened to me or to someone I know, and they display the joys and horrors of little places that don’t often get talked about.

When I wrote the first draft of this book, I gave it to some local friends and asked them to be honest. Was I being too cruel with these pieces of local lore? Should I back off? Are people going to be livid?

They all told me I hadn’t gone hard enough and asked me to include their own personal horror stories.

All of a sudden the work became a memorial. A catharsis for real people in my life. Penny Harbour stories are often—but not all—dark. Some are very hard to look at. They felt impossible to write. I almost didn’t. But if I don’t have the courage to tell those stories, who will?

It was important, and I’ve been blessed that early readers have seen the depth of those points of view. People have expressed feeling seen and heard, have wanted to rescue characters from their scenes and sweep them off somewhere kinder. And that’s all that I’ve ever wanted from this career.

A lot of my work is about addressing real struggles from a fictional lens and allowing readers to work through those things for themselves. That was always my favourite thing about reading fiction; seeing my struggles in the pages in a way that made my life feel a little less dire. Coal Gets In Your Veins is about grieving and change, but it’s also about courage. Change is hard. Stepping away from what you know is hard. And as the series continues, the question remains: how do I live with this change when I don’t know how to live any differently? What do I do with all this grief I’ve been given when I don’t want it anymore?

But that’s a story that remains to be written.

I suppose the only remaining question is “Cat, why vampires though?”

Because vampires are fucking awesome, Bob. That’s why.

But there’s a serious answer too.

I was obsessed with Buffy the Vampire Slayer growing up. Spike especially. From the perspective of an awkward teenager, he was a cool guy with an emotional availability that most other characters didn’t have. He was evil, sure, but he loved hard and deep, and what impressionable young girl doesn’t want to be swept away from her troubles by someone who would do anything to prove how much they love her? (Including but not limited to smiting all your enemies.)

I wanted to bring some of that into this concept and give space to the idea of rescue and kind, reciprocal love. It took a bit to get it right. When I was initially writing Coal Gets In Your Veins, something about Spencer had fallen flat. I knew it in my bones, but not why. And then I put 250 hours into Baldur’s Gate 3, fell in love with Astarion, and knew what Spencer was missing. Spencer went from a deeply masculine brooding shadow in the woods to a bisexual snarky effeminate fop that likes Stardew Valley and cassette tapes and driving too fast. And the response to that from my readers has been very rewarding. Turns out there are a lot of people out there looking for queer vampires who will snark liberally, defeat their demons with them, and also tuck them in when they’re cold and tired.

The combination of concepts allowed me to build a flawed character who hadn’t learned how to be obsessed with someone, but how to love and hear and care. And isn’t that what most of us are searching for in the end?

Speaking of which, I also do try to be sweet and cute and funny, I promise. My work isn’t grimdark, and I deeply believe that humour—even the darkest of humour—is essential for making it out of any situation intact. The entire cast—but especially Laurel’s friend Mary-Jo—is equipped with a funny bone and aren’t afraid to use it.

This book is an odd combination of things, and it’s my hope that I’ve managed to weave it together in a way that readers find interesting, thought-provoking, and moving. I think most authors finish a project, think I hope I pulled this off, and send it out into the world. This book is no different.

I can say without a doubt, this one comes from my bones. Pieces of me live in every chapter, in every character. I’m proud of the work.

Though it stands to cause some ripples, I think it’ll be worth it.

Most difficult things are.

Interested on what you've just read? You can order Coal Gets In Your Veins using this link.

About Cat Rector

Cat Rector grew up in a small Nova Scotian town and could often be found simultaneously reading a book and fighting off muskrats while walking home from school. She devours stories in all their forms, loves messy, morally grey characters, and writes about the horrors that we inflict on each other. After spending nearly a decade living abroad, she returned to Canada to resume her war against the muskrats.

When she’s not writing, you can find her playing video games, spending time with loved ones, or staring at her To Be Read pile like it's going to read itself.